When the Eiffel Tower was a subject of controversy

Thursday 24 August 2023

Modified the 24/08/23

Nowadays, the silhouette of the Iron Lady has become very much a part of the Parisian landscape. But Gustave Eiffel had to fight tirelessly to impose and complete his plan to build a 1000-foot metal tower, which would come to be known as the Eiffel Tower! As we are paying tribute to Gustave Eiffel in 2023, to mark the centenary of his death, let’s look back at the fights he waged for his tower, which was the focus of much debate and controversy before even being built.

“Eiffel, Higher and Higher”: to learn more, come and discover the incredible race to construct the highest building in the late 19th century, in which Gustave Eiffel was one of the main competitors, by visiting the free exhibition on the Eiffel Tower esplanade (accessible to all, no ticket required), created by Savin Yeatman-Eiffel, Gustave Eiffel’s descendant.

From June to December 2023.

The rivalry for the 1889 World Exhibition

It was no walk in the park for Gustave Eiffel to have his metal tower project chosen. A number of years before the 1889 World Exhibition, the idea of building an enormous tower was born. It would be the major attraction of the fair, which had important aims for France: to celebrate the centenary of the French Revolution, unite the population and show the entire world France’s strength in engineering and industrial expertise. And Eiffel had a serious rival: Jules Bourdais. This highly respected architect was at the height of his glory: he had won the competition in collaboration with Gabriel Davioud to build the Palais du Trocadéro (now destroyed and replaced by the Palais de Chaillot), which was the highlight of the 1878 World Exhibition.

Jules Bourdais proposed a competing project for a monumental, 1200-foot tower, made out of granite and porphyry and topped with a powerful beacon, named the Sun Tower.

The two projects were total opposites: stone versus iron, an architect versus an engineer, classic versus modern... The battle took place in the press, with Eiffel and Bourdais mobilizing their respective supporters. Early on, Gustave Eiffel placed the emphasis on his ability to build his tower within a realistic timeframe and at a controlled cost. He also used a patriotic and utilitarian argument that the Tower “will provide essential services to science and national defense”.

Jules Bourdais also used the press to create publicity around his project. But he lacked credibility: would it really be possible and financially reasonable to build such a tall stone tower? It didn’t seem likely.

However, in 1886, victory seemed within grasp for Jules Bourdais, with support from new Prime Minister Charles de Freycinet. But Gustave Eiffel wasn’t giving up... He turned to the new Minister for Commerce, Edouard Lockroy, who was responsible for coordinating the 1889 World Exhibition. Lockroy was unconvinced by Jules Bourdais’ project and won over by the arguments of Gustave Eiffel, who also stated that he would finance the entire project in return for receiving a contract for the tower’s operation.

On May 1, 1886, the Minister launched a competition for the contract to build attractions for the Exhibition. Among other things, candidates were invited to “study the possibility of building a 1000-foot iron tower with a square base with sides of 410 feet”. It would seem that this proposal was custom-made for Gustave Eiffel’s tower. Caught unprepared, Jules Bourdais participated, replacing stone with iron for his Sun Tower. But in the end, the project by Gustave Eiffel and his architect Stephen Sauvestre was selected for the 1000-foot tower competition.

Protests from artists during early construction

However, Gustave Eiffel’s problems were just beginning. And after winning the competition, his project was subject to multiple attacks. Firstly, from architects, who were outraged to see an engineer chosen for such a project. Then, the Parisian artistic scene got up in arms when construction began. On February 14, 1887, the famous “Protest against the Tower of Monsieur Eiffel” was published in Le Temps newspaper, calling on the person responsible for works for the Exhibition to put a stop to it. The letter was signed by major names in the artistic and literary world: composer Charles Gounod, writers Guy de Maupassant and Alexandre Dumas (son), and poet François Coppée, as well as classical architects like Charles Garnier, who designed the Opéra Garnier.

“We come, we writers, painters, sculptors, architects, lovers of the beauty of Paris which was until now intact, to protest with all our strength and all our indignation, in the name of the underestimated taste of the French, in the name of French art and history under threat, against the erection in the very heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower which popular ill-feeling, so often an arbiter of good sense and justice, has already christened the Tower of Babel.”

Gustave Eiffel responded to this diatribe immediately: “I believe, for my part, that the Tower will have its own beauty [...] Is it not true that the very conditions which give strength also conform to the hidden rules of harmony? [...] Now, what condition have I had, above all, to take into account in the Tower? Wind resistance. Well! I claim that the curves of the four edges of the monument, as calculated [...] will give a great impression of strength and beauty. [...] Furthermore, the colossal has an attraction, its own charm.”

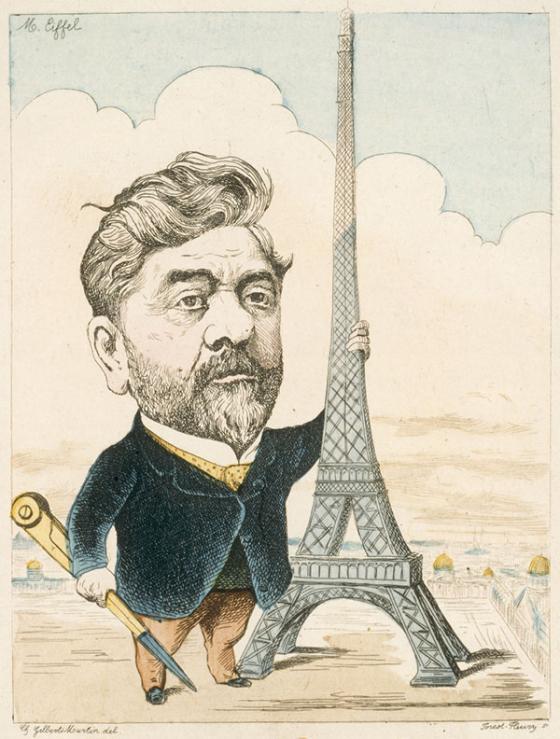

It should also be noted that the engineer was the subject of many caricatures in the press at the time.

Parisians didn’t like the Eiffel Tower?

The construction of a giant iron tower in the middle of Paris sparked contrasting opinions from Parisians, who at first were rather doubtful about the aesthetics of the Tower under construction. The influence of artists, who were not shy to criticize, also fed into the reluctance of residents of the French capital: “this belfry skeleton” (Paul Verlaine); “this truly tragic street lamp” (Léon Bloy); “this mast of iron gymnasium apparatus” (François Coppée), and so on...

Famous author Guy de Maupassant called it a “giant ungainly skeleton [...] aborting to form a ridiculous, skinny, factory chimney stack”. After the Iron Lady was built, he was seemingly still repulsed by it - he said that he often went to have lunch on the first floor of the Eiffel Tower, as it was “the only place in the city where I won’t see it”.

However, the supposed hatred of Parisians for the Tower had little foundation, apart from the concerns of Champ de Mars residents for their homes. A Paris City Council member living in the area launched a lawsuit against Gustave Eiffel, who, to avoid stopping construction, declared himself prepared to personally assume all risks and compensate locals in the event of an accident. Fortunately, it wasn’t necessary!

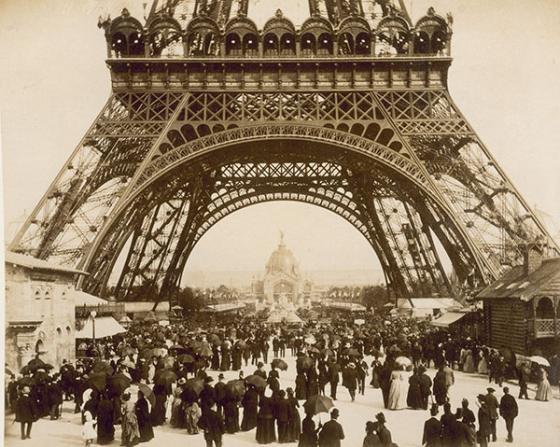

The Tower opened to the public on May 15, 1889 and was immediately a grand success, triumphantly welcomed by crowds of people, French and international, sweeping away all previous controversy. Some of the disparaging artists even made public apologies. And the Tower was definitively adopted into the hearts of Parisians, proud of this symbol of modernity. It became the icon of Paris.

Gustave Eiffel’s final battles to permanently safeguard his Tower

Even if the entire world covets our Eiffel Tower, some detractors weren’t ready to let go of their grudge, such as architect Charles Garnier. In 1894, a new call for projects -partially drafted by Garnier- was launched for the 1900 World Exhibition that would be held once again in Paris. Applicants were granted full freedom to modify or even destroy the Eiffel Tower! No project - and some were particularly farfetched - would be selected and the Tower would remain intact, at the center of the new, spectacular installations in 1900.

However, the Tower was only meant to stay up for 20 years, under the operation contract held by Gustave Eiffel (until December 31, 1909). Danger was creeping closer, and furthermore, visitor numbers to the monument were down. In 1903, demolition was seriously considered, as the Paris City Council wished to redevelop the Champ de Mars. In the end, it was decided not to destroy the monument. However, Gustave Eiffel pushed, financed and promoted all the scientific experiments that took place at the Tower: meteorological observations, wireless telegraphy, falling bodies, aerodynamics and more... The scientific uses of the world’s highest tower undoubtedly saved it from destruction. And above all, its strategic potential: in 1903 and with Eiffel’s support, Captain Gustave Ferrié installed a military network of wireless telegraphy, a fast-growing form of communication technology. The range for wireless telegraphy grew from year to year, and the strategic importance of the Eiffel Tower station became evident, capable of emitting and receiving long-distance signals.

On January 1, 1910, the contract granted to Gustave Eiffel was renewed for 70 years. The Eiffel Tower was saved, for good!

You liked this article ? ? Share it

Opening times & Ticket prices

Today :

09:30 - 23:00

Price :

28.30€

Take Paris’ most spectacular ride to the top for €28.30 or less (€28.30 for adult ticket with access to top by lift).